How the Words

“CHRISTINAUX au KILISTINO”

appeared on the

1720

Carte du Canada

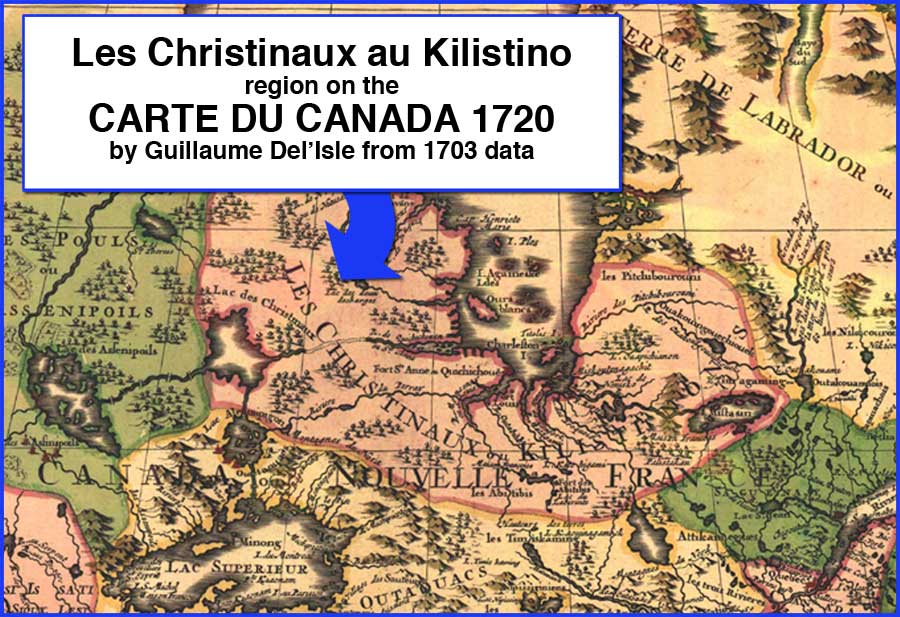

During a period from 1708 to 1720, the words, “CHRISTINAUX au KILISTINO” were put onto the 1720 Carte du Canada by the Guillaume Del ’Isle of Paris, France.

Christinaux seems like an odd spelling. Did the French explorers in the 17th century know how to spell the English word for Christians?

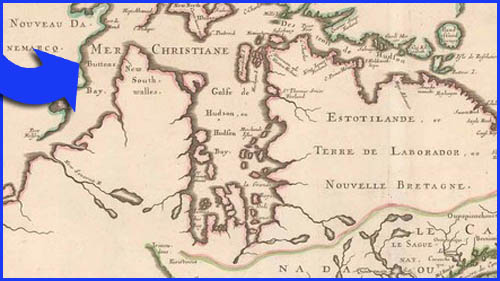

The French at the end of the 17th century knew how to spell “Christiane”. In 1619 an explorer, Jean Deani, wrote “Mer Christiane” onto a map. Deani’s information may have been the only source for the “Mer Christiane” label near the mouth of the Nelson River on a 1656 map entitled “Le Canada au Nouvelle France.”

|

| Le Canada au Nouvelle France |

That label might have been consistent with the behavior of descendants of the Lenape, who followed Christ’s ethics. Some of those descendants may have remained near the Nelson River after the main group had moved away over two and a half centuries earlier.

Jean Deani’s documentation may have been one of the reasons why the 1687 map prepared by Rocci of Rome had the whole Hudson Bay labeled “Mer Christiane.” But other explorers were also coming to “Mer Christiane.” An English ship, the Nonesuch, over wintered in the south portion of James Bay during 1668-69. The Hudson's Bay Company was founded in England in 1670.

The “Christiane” label for the Bay was probably a concern for English investors in the Hudson's Bay Company. In the late 17th century many of the Christians in England believed that English explorers should behave better than the Spanish Catholics. The Spanish in America had committed numerous atrocities, including the massacre of French at Fort Caroline in 1565.

Most English charters had a phrase prohibiting settlement in Christian areas. The King of England tried to enforce that doctrine because the devout Christians in England expected English colonies in America should avoid areas where Christians or Catholics were already living.

That situation may have been one of the reasons that the Hudson's Bay Company advocated that the proper name for the bay was “Hudson Bay.” The name “Bai D’ Hudson” does appear on the 1720 Carte du Canada. But the French map makers kept the original the “Mer Christiane” label along with Deani’s name and the 1619 date. That data was moved into the Arctic, north of Baffin Island. The French spelling of “Christiane” is still on the 1720 Carte du Canada, but in a location where most modern map viewers judge the label as absurd in an impossible location.

If French knew how to spell “Christiane”, why did they not use “Christiane” below Hudson Bay on the map?

The map makers may not have used “Christiane” on the land south of Hudson Bay for similar reasons. The Hudson Bay traders may have heard the word “Kilistino” from most of the local people. The traders may have concluded that “Kilistino” was the word from which the first French explorers came up with “Christiane.” But the Hudson Bay officials may have believed, for geo-political reasons, that “Kilistino” did not mean “Christiane.” To the Hudson Bay traders the proper label for the people in the region may have been “Kilistino.”

Is “Christinaux” just an alternate European spelling of “Kilistino?”

It appears that the map makers thought so.

Does “Christinaux” mean “Christians?”

Some of the French in America may have advocated that “Kilist” may have meant “Christ” as in “Christiane.” But the map makers in France probably thought that there were no Christiane in America before Columbus. That concept was written into the European history books before 1700. So, perhaps, they chose the compromise solution. They put “Christinaux” on the map as a variation of “Kilistino.”

The English colonists, who wanted to believe there were no Christiane in America before Columbus, may have explained that “Christinaux” was just a variation of “Kilistino.” They might have insisted that “Kilistino” did not mean “Christiane.”

So four centuries have passed. Now almost everyone, including most Christinaux and Cree believe that “Christinaux” does not mean “Christians.”

Is that belief correct?

Recently an American (Indian) friend wrote that “Christinaux” is a corrupted French word for the Cree word “Kiristino.” But the “Kiristino” meaning could not be found in the modern Cree dictionaries.

Still “Kilistino” is the word shown on the map. The Lenape had difficulty with “r.” Speech patterns learned from childhood made it difficult for Lenape to say “r.” The Lenape use “l” in the place of “r.” The Blackfeet have several cultural traits that imply they descended from the Lenape. One of the most prominent traits is that the Blackfeet have no “r” in their language.

Without intending to, the map makers did confirm the “kilistino” was a Lenape word. Sherwin, Vol. 1, p 40 explains that ‘Kristino,” which is an obvious alternate spelling of “Kiristino,” is the Old Norse word “Kristina,” which means “Christians.”

So “Christinaux” is really a variation of an Old Norse word for “Christians.” The English, as it turned out, would exploit the “Kilistino” because they thought there were no “Christiane” around. Christinaux and Cree are still second class citizens in a Christian country.

But, as time passed, the name “Christinaux” may have caused too many questions like, “Are those people, Christians? English domination of Cree lands was more acceptable than domination of Christians would have been. The word Cree is now used for most maps and books for the area south of Hudson Bay.

The English in Canada, today, call the people their ancestors found south of Hudson Bay “aboriginals,” which means ”people inhabiting a land from a very early period, especially before the arrival of colonists.” But the modern word “aboriginal” also implies “there were no Christians in America before Columbus.” True. The Christinaux and Cree today are, by definition, “aboriginals” but they are also descendants of “Kristina,” who were the first Christians in America.

Many of those modern aboriginals are Lenape or other Christians. Their Christinn culture has been in Canada twice as long as the Church of England has been. A more appropriate description for the Lenape, Cree, and Christinaux would be “descendants of America’s original Christians.”